The Written Thesis for my exhibition Hollow Myth

My Written Thesis

The American fine art thesis is supplementary to the show. The thesis exhibition is the final thesis. The goal of the written thesis is to provide a conceptual context for the work, and to explain artistic processes. Instead of coming to literal conclusions, I wrote loosely setting a mood in which to consider my work. This absolutely bewildered my editor when I handed her my paper. She asked me, "Where is the rest of it? What the hell is this?" I had a good laugh and realized how long I had been submerged in the art world. I had forgotten this type of writing isn't standard. Hopefully, this will provide the correct context in which to read the thesis.

Hollow Myth

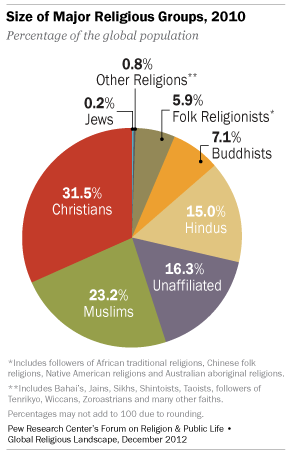

I don’t have an answer for why I am alive, or for what purpose I am alive, and according to the Pew Research Center, as of 2015, this view was shared by 1.2 billion people internationally. People around the globe are embracing their ignorance, and willingly live in uncertainty. We watch the great religions of the world fizzling-out like a fourth of July sparklers, and what remains for us is speculative spiritualism, and half-hearted ceremonies. As someone who has been repressed by mythology (i.e., Southern Baptists), as we all (i.e., Religion, Cultural Norms, etc.), my teenage years were a reaction against my culture. Now that I am an adult, I wonder, should I stand by and let these myths die, or should I take cuttings from the best trees of my childhood and grow a new cultural orchard? I think the orchard is the best option. Even though I have mercilessly picked apart my traditions, I believe I still don’t understand the full extent of how vital these mythologies are. Western painting is one of these great mythologies of my childhood. My first interactions with art were through art history text books of Renaissance and European painting. Through my classical painting education I received in Italy, I made contact with these art histories, and absorbed their traditions which now live through me. As a classical artist, I will be deciding what aspects of it should live and should die. In my art practice I have taken my choice of clippings from western painting and I am growing them in the soil of contemporary thought and experience. Somehow the old tradition still speaks to me in modern times. The frescoes of Piero della Francesca can hypnotize my modern eyes. Look around at this transitional world we live in. Crucifixes now hang in museums. My angels are orbiting satellites beaming down messages to my smartphone. On rockets, modern man broke into the heavens riding flaming science and found no Gods in the sky, only a cold abyss. Humanity is its own God and artificial intelligence is our Man. I no longer live in fear of a God, instead I cope with my uncertainties. And as the Gods of the Earth, sadly we have found ourselves to be quite cruel and negligent. What mercy have we shown the animals? And with what nonchalance have we trashed this Eden? So, I am writing my own mythology of uncertainty and ignorance, in the language of western painting because western painting’s history offers a depth of expression that the new digital media cannot. If a photograph is worth a thousand words, a painting is a direct window into the mind. And my thesis exhibition, Hollow Myth, is just that, a window into my mind. The ambiguities of these paintings are an expression of my own experience. My experience of living in a time of hollow myths. The crucifix no longer has a soul, I just see empty plaster hung on the wall. The American flag is just cloth whipping in the wind. God is dead, and life is just a thing that is happening. I hope my paintings have the same deflated grandiosity of a Vatican City gift shop. This is what it feels like to be me, living now. These paintings document the daily qualia of my self-observations. I believe my experience is common. For now, my paintings are an attempt to reflect on my experience of hollowness, but over my career, I hope to create something for myself to believe in.

The Painted Space

A bipedal animal smeared campfire charcoal and wet river clay onto a cavern wall and began recorded history; that was the day we became humans. Painting allowed mankind to transfer thought and feeling into a semi-permanent body which could long out live the artist. The invention of painting made humans the first animals to break free from the cycle of natural selection, and take evolution into their own hands by creating inherited culture. A circle with rays around it became the sun. A line with four projecting lines and a circle on top became human. These messages on the walls evolved into writing, for example, Egyptian hieroglyphs and ancient Chinese script. Markings in the mud (i.e., Cuneiform) became a means of accounting, which allowed for commerce. Thus, from cavern walls evolved Hammurabi’s code, the Tales of Gilgamesh, the Book of the Dead. We all inherit thousands of such mythologies, which allow the diverse people of the world to agree on a common set of beliefs, enabling a large group of strangers to come together and cooperate. Painting is where it all began. The painted space is where the myths were created. The painted space bridges perceptions. As a painter, I would like my art to reveal the function of painting, as well as to reflect on how much of our daily lives are imagined. This doesn’t mean I am anti-myth or anti-art, quite the opposite, I think mythology is the second greatest invention after painting. I believe art’s job today is to enlighten, and this means exposing myth as myth. Every now and then it is necessary for us to remind ourselves that we are living out stories. There is hope in these revelations that things can get better if we author the stories ourselves. We must master our mythology, rather than falling victim to its dogma and letting history drag us around by the necks. Exposing artifice is a major component of all contemporary art today. I am simply joining the call. Yes, these ideas that rule us are stories we tell ourselves. Yes, they are heading us down a path of destruction. But look, it is all just a myth. Now who do we want to become, and what will be our story?

The Artifice of Perception

The practice of painting has shaped the way I experience the world. The long hours I have spent observing an object, and the many attempts to accurately represent my perception of that object has revealed to me the artifice of my perception. I have found that to achieve a convincing illusion, one can’t simply copy what they see. We actually see very little, and because of this, painters take all kinds of short cuts to achieve an illusion. Look at the blurry paintings of Velazquez, somehow his figures seem realer than the people in the room. To the untrained eye, a Velazquez up close looks like puerile scribbles, and smudges. And from 15 feet back, the perfectly placed brushstrokes transform into air, light, form, and soul. Velazquez has grasped vision, and instead of painting in prose, depicting every detail, he paints in a poetic shorthand. These are the secrets of the craft. Just like a good magician, a good painter can lead our attention and make us believe in illusion.

The light reflecting off an oil painting can never equal the intensity of light (i.e., value range and color intensity) in nature, but somehow the trompe l'oeil painter manages to fool us. Over the course of my realist training, I learned how to dissociate light from vision, meaning how to not see things, but to see the shape of things. Our vision is an intricate mosaic of shapes containing specific color-values. If I can copy the exact shapes and their color-values I can make you believe in an illusion. Even more convincing is accurately expressing the edges of those shapes on a spectrum of hardness and softness. The softest edge being those of a misty cloud. The hardest edge being those of a razor blade. And if you want to take the illusion one step further, one must accurately copy the relationships of all shapes, edges, and color-values to one another within the visual field. For example, stating what is my warmest warm, what is my reddest red, what is my blackest black. Now on a spectrum, how does this blue here compare to my bluest blue, and so forth. The relationships of color-values of the abstracted visual field must be compressed into the value and chromatic limits of the pigments of oil paint. Cameras go through the same process to create a jpeg. A photo must work with the value and chromatic limits of the printing inks, or the intensity of light from an illuminated screen. We can see how a camera compresses light in settings of both intense and low lighting, such as a sunset. The sun will appear as a burnt-out white circle and the clouds will be a charred black brick. Because of the extreme value range of the sunset, the camera fails to accurately compress the values. So, a good painter knows the sun should be our lightest light, the sky is our secondary light, the clouds are tertiary light, etc. Our minds also compress vision. We can observe the compression of our minds after a long walk outside under the sun. When we come indoors, burnt-out white shapes appear in our vision, just like those of the camera sensor. These are just the mundane ideas the realist painter must know. The problem of interpreting our perceptions is much more interesting, meaning: What do these shapes mean?

I have observed that I project myself onto the world. For example, the sunset we have been trying to record, why do I want to record it? Why is the vision of a sunset significant? Because I find its arrangement of colors to be beautiful. Beauty is a subjective concept, meaning no single definition exists in the world. Beauty is something I project onto that particular sunset. Something in the sunset’s specific arrangements of shapes of color-values has aligned with my internal conception of beauty. This phenomenon of perception awakening affection and association is mysterious, but the painter must solve these mysteries in order to communicate to an audience. Visual interpretations and associations are how the painter can add subtext to an image rather than being literal. This difference is the same difference between prose and poetry. Are you an artist if you only document what you see? No, the art happens in the subtext, meaning the things left unsaid.

How we interpret what we see is guided by biological evolutionary responses, communal cultural responses, and acquired personal responses. As far as biological responses, have you ever mistaken a stick for a snake? Before you have even become conscious of the stick, the mind has you leaping in the air from fright. As for cultural responses, can Americans view a painting with mainly reds, whites and blues and not relate it to their nationality? And for personal responses, I can’t ever see a flicker of light on water and not think of my childhood home. The intricate textures of my perception are what fascinates me, and painting allows me to explore that texture in depth. Though examining the texture of my perception, I can discover myself through the external world.

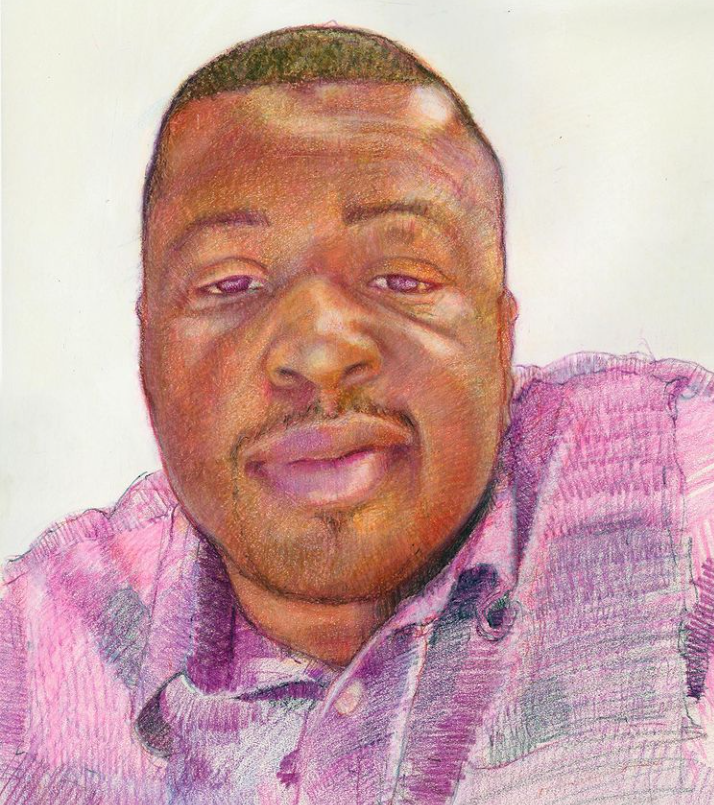

Now, if a painter manages to actually figure all this out, and is able to use this knowledge to communicate through paint, what then should one say with it, and why say it through paint? As a westerner, the genre of western oil painting requires a certain type of looking from me. Western painting is a grand stage that demands serious consideration. I am using this preexisting mythology to my advantage. Maybe we could think of it this way, painting is Christianity and digital art is Scientology. Most people don’t take Scientology seriously because there is no history behind it. So, in a painting, the viewer knows, “Yes, you are lying to me, but because of my ingrained culture, I am willing to suspend my disbelief”. Whereas with the genre of animation, the viewer thinks, “Yes, you are lying to me, but I enjoy fantasy”. Painting is ingrained in our psyche, and it demands respect. Culturally, painting also is an old art form which asks us to spend time with it, like a novel. Unfortunately, modern Man shields their vision of the painting through the screen of their iPhone, and quickly converts it into the comfortable digital-space they are used to. They don’t want to give into the demands of this ancient authoritarian. Painting for them is a brief moment lived and documented. They aren’t willing to confront the challenges of abstract thought, and opinion formation. For them images exist as a brief dopamine dump, an escape from boredom, a comfortable distraction. When we view a painted-space the proper way, we are entering the greater realm of philosophical imagery. A world we have been creating for centuries. We must confront this silent plane, and its ambiguities, and we must resolve these ambiguities for ourselves. In this way it is conversational. An opinion is presented and considered, and a personal opinion is then formed. The painted-space is different from the photo-space, or the video-space; we have separated it out in our minds. This platform is the main aspect of Western painting I want to keep alive, and the primary reason I create oil paintings. I also want to keep its intimate tradition of craft, and the piercing observation of realism. What I will let die is the legacy of white supremacy, propaganda, and its dogmatic aesthetic. Unfortunately, this European painted-space will always carry this baggage, but my hope is that it will one day become a global space for all to enter and inspect themselves. Artists like Kehinde Wiley have taken on these aspects of the tradition, and are now making an entry point for BIPOC people. Kehinde has taken his cutting and is growing a new tree of culture. The contemporary German painters have used western painting as a way to reflect on their past. Nazism used the weight and authority of western painting to support Fascism. They created the genre of painting called Social Realism as a means of propaganda. Artists like Gerhardt Richter, Anselm Keifer, Sigmar Polke, Georg Baselitz all grew up in post-war Germany, and were trained in Social Realism. These artists have since transformed this language of Social Realism from propaganda into a visual philosophy to help their people navigate and conceptualize the weight of their past. I like to think Germany could not be what it is today without their paintings. This type of self-authoring mythology is what I hope for the future. These deep-seeded cultures can be a tool for change and evolution. Let’s work with what we have and nurture it, rather than executing it. This is the job of contemporary artists and philosophers. They are the ones who are rewriting mythology to guide the present.

Our lives are the stories we tell ourselves. Most people do not realize their power to rewrite their own stories. I want to call attention to this by showing the artifice of our perceptions through western realism; I hope my paintings can demand a moment of meditation. My imagery asks the viewer to observe their ability to deceive themselves by showing the strings, wires, and projections. It is a direct metaphor for what we do every moment of the day. We all possess the incredible ability to imagine and to project ourselves onto the world. We all are so good at it that we completely believe in our illusions, and the characters we play. All the seams, wires, strings, and props of our perception are all perfectly hidden from our viewpoints. Only in rare moments of great disruption do we see the seams in our story and in history.

The Tremendous Joy of Simply Being

FOR the past several years, my mind has explored the nooks and crannies of Existentialism. I have found these mental spaces lately to be inhospitable, and I’m beginning to take my therapist’s advice, ‘Don’t stare at the Sun, or at death’. I have run myself ragged trying to understand the hows and whys of life. As well, I have attempted to understand my life and my experience. I can’t. I’m just a fool on stage with no idea who I am or what the hell this is all about just like everybody else. I have pursued self-improvement, education, therapy, medication, and on and on without any great enlightenment. And after a year like 2020, I think all of us are worn out from the abundant fear and stupidity of the world. I don’t have any big concepts for change. I have no idea what will make things better. But, after all this nonsense, I believe I have arrived at a compelling perspective, things are; no hows or whys about it. Things are and it’s fascinating. Painting is a medium that takes me deeper into the way things are, and the way I am. I observe the stream of my perception through a painter’s eye. For example, the quiet joy of shapes of light projected onto the walls from the window, the burning red of a fall leaf, the gentle sway of grass in the wind, the flickering images I conjure when I daydream, the specific mood in someone’s eye, the dance of light on moving water. It’s all incredible and just is. I want my painting practice to be, like everything just is.

Innate Studio Practice

I had studied all summer before I moved to Alfred, NY to begin my masters. I had organized all of the concepts I thought I would be making art about into concise ideas. I even planned several paintings. So, when I arrived, I did make art about those concepts, and the paintings were ok. There came a point when I gave up on my ideas, and for the first time in years, I made a massive, unbelievable mess. I started pouring plaster directly onto the floor and throwing pigments onto it. I slung stand oil around like Jackson Pollock. I worked like this for months, and my dirty footprints lined every hallway. After the semester came to a close, I had to chisel the floor back to smooth. That was a critical moment when all personal myths of what an artist is, what art is, and who I should be as an artist, collapsed. It was the first time I had fun painting in years. I rediscovered the sensuality of dry pigments, the translucence of oil, the smells of paint, the gestures of creating; I’m in love with it all. I brought that joy back to realism. The infinite joy of observing the fall of light. The challenge of describing it in the flick of a wrist. I thought, why stop? How do I want my days in the studio to be? Should I feel like every day I am climbing Everest, or could I be a child in a sandbox? I kept working like this into the next semester and I found concepts were coming about naturally from making. I developed faith in myself, and that through my practice the art would come. This is now my practice. It is the natural way of working. I don’t block myself. If an idea arises, I make it.

This innate art practice is intuitive, and I believe that intuition is a synthesis of years of lived experience and thought, into singular guiding emotions. Intuition is a short cut, an energy saver. I have faith that there is a logic in my actions; it is up to me to interpret my actions correctly. My concepts come after the fact, after periods of intense making. I then spend a long time analyzing the art, and discover what in the hell it is I have been doing. I know it seems completely backwards, but the ideas that arise from intuitive work are more sophisticated than anything I could consciously plan. All I have to do is play.

My Studio Practice

Automatic studies

The first phase of my art process begins by finding an image through studies. These studies are done using automatic methods of the French Surrealism also known as Automatism: an attempt to capture the pure stream of thought, free from aesthetic and rational constraints. I use these methods because they allow for my imagery and concepts to evolve. I hope that each painting can be a new exploration, under the umbrella of my thesis. Automatism also reflects my current mental states, which become entangled with each study. Through the studies, I explore what it is like to be me at that moment, what I can do with paint, and new angles on my concepts. The automatic studies are done in many mediums: crayon, paint, plaster, GAN imagery. These studies are play time. There are no rules, or judgments; I just make. This type of play is sincere, meaning I don’t play frivolously; it is an honest effort to make something meaningful.

After making some studies, there will be only a few with obvious significance, the rest are discarded. What the significance is, I am not always aware, but the study will create a visceral response that summons an interesting mood, emotion, thought, or memory. Through this process I am exploring myself. I am looking for answers to who I am, and to what is happening inside. My eye is my guide.

Building It

Once I have created a study of significance, I build it. This phase is still a form of automatism, but it is directed toward fleshing out the image. I try to recreate the image in a 3-d form, usually in plaster, or fabric. This process takes away the ambiguities of the study and gives the idea the thusness[1] of the natural world. These grand ideas take on ordinary bodies that humble them. This building process also allows me to spend time in the mental space of the image, and to really feel what is there.

Framing It

Now that the object or scene is created, I place it on my still life stage. I must find the correct viewpoint, light effect, and framing of the object to amplify its significance. This process involves an extensive photoshoot of the object from many different angles and under many different light sources. I find it’s best if I don’t think so much and just shoot. When I have taken a sufficient number of photos; I scroll through them on my laptop. Usually there will be one or two that make a statement. These images pass on to the next step.

Editing It

Those few images that made the cut now go through the final round of the beauty contest. I upload and edit the photos in Photoshop. First, I perfect the light effect and color balance, and then I go on a journey with them. I throw in unexpected colors, edit things out, digitally paint on top, etc. I do this because photos don’t always translate into paintings. I must make it an image that suites paint, and also, I can take big risks in Photoshop with no consequences. This thorough process lets me decide what exactly I want to say with the painting.

Grounding It

Now that I have decided on the image and its scale, I begin building the canvas or wooden panel it will be painted on. This phase of the process allows me to prepare my mind for making the image. It gives me time to let the image sink into my psyche. I can plan each step of the painting in my mind, and hold it there. Every time I build a panel or canvas I also try to improve upon its stability and archivability by solving problems from the previous canvases and panels.

Drawing It

I draw the image several ways, either through free hand drawing, or through scaling up the image through grids. I begin the drawing in charcoal, and then move into paint. This under drawing consists of proportionate contour and shadow lines. I solve all the proportions in this stage.

Painting It

Finally, I can begin painting. I premix the colors needed for the day on my palette. I begin painting the color masses in all the major shapes. I first go for the visual impression, and slowly work toward specificity. The early stages of the painting are simply copying the digital image from my illuminated laptop screen. Once I have achieved a relatively accurate copy, I begin focusing on what the painting needs. After departing from the digital image, I reconsider everything and will often paint out of my head. I will make up folds, blobs, colors, shadows, or whatever is needed to reach the images ultimate significance.

[1] This idea of thusness is taken from Mahayana Buddhism to describe the ineffability of reality. Through the term’s intentional vagueness, one can simply note the nature of reality’s being without endlessly conceptualizing the incomprehensible.

The Theater of Perception

I had never seen the actual “Dream of Constantine” by Piero della Francesca, but the printed image was strong enough to hold my attention for many years. The yellow-and red tent illuminated by a swooping angel haunted me. Something about the way the tent opened has a deep significance that I cannot put into words. What a great mystery it presented. I wanted to explore my quale of looking at the image of “Dream of Constantine”. I hoped to discover what the significance was inside me that I was projecting onto the image. Somehow the image was the only link I had to that internal space, there wasn’t anything that felt similar. I began by building the motif. I dipped a cotton cloth into wet plaster and draped it over a stick. I ran wire from underneath to give structure to the rising folds and cut a slit up the center. Once it dried, I hung it on my still life stage and projected the image of the fresco onto it. You see, this is what I had been doing in my head, projecting inner significance onto something real, and now I had brought that internal process into the physical world so that I could observe it externally. But, now that the sculpture and projected image was before me, I thought, here is the stage of my perception, the grand theatre in my head. This needs to be a painting, and by painting, I will further abstract the experience by attempting to translate it into a philosophical image. This layering of reality, projection, and translation is exactly what I am doing all day in between my green eyes.

A Fool on Stage

“All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players”–Shakespeare

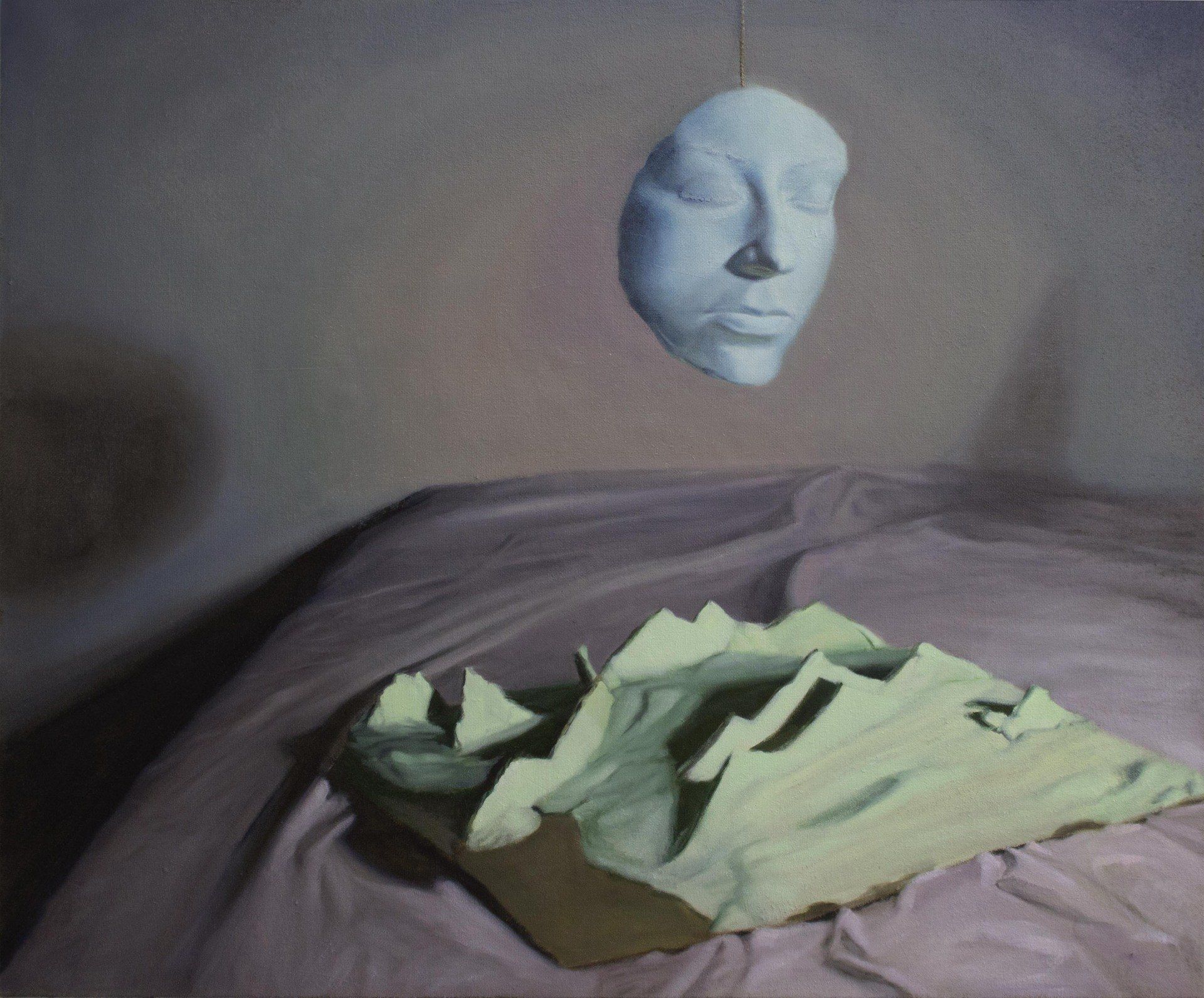

This quote by Shakespeare is another artifact of great significance to me. It cuts straight to the core of my fears and my experience. I wanted to penetrate this idea, so I made a painting about it. The word persona in Latin means mask, and also a character played on stage. It is the root of the word person, and personality. Sometimes, I have many personas for the different circles of my life. It is not always appropriate to fully show myself. I must edit and read the room, as we all are doing, and the ones who cannot do this suffer socially. So why not begin this project by building a persona. Luckily enough, Maddy[1] was willing to lend me her face for the project. I cast her face on the lunch room floor in alginate with a plaster mother mold. After a careful unpeeling of it from her face, making sure not to remove her eyebrows and eyelashes, I cast several personas in plaster. I submerged string into the backs of them so that I could hang them on my still life set. And suddenly there I was, a face of egg shell white, sleeping, simultaneously full and empty. The sacred persona, the lead role in the story we tell ourselves, hollowed out into a cold shard of plaster. I love its absence. An absence that allows the mind a space to fill. The absence I am after is the feeling of entering someone’s messy bedroom without them there. The feeling of looking at a corpse. The feeling of turning a street corner and suddenly being completely lost. The feeling of looking into a Greek Bronze’s empty eyes. The feeling of standing on ruins. The feeling of walking through hurricane wreckage. It is harsh, lonely, mysterious, and strangely beautiful, a deep and unexpected beauty. I suspended the persona over the fabric draped stage which became a bed to dream a life on. It needed to be ordinary and thus. And beneath her I placed the world, a radically simplified world of cut up cardboard slapdashed together and glowing a synthetic green. The role this persona plays is the fool, a person who suffers from their ignorance. A quixotic fool who lives in a great fantasy of their own, and to be awakened from this fantasy is to lose all meaning in life. At least Quixote has something great to live for. Thus, I once again took something internal and brought it outside so that I could understand.

[1] Madeleine Willis, a first-year graduate student of the Alfred-Düsseldorf Painting MFA.

Projections

The group of paintings I call “Projections”, are probably misnamed because most of the imagery was imagined by artificial intelligence (AI). I used an AI model called a GAN image generator as a tool to expand my creative horizon. To make this image-generating AI, I first had to compile a dataset of example imagery. I have made many AIs, but for the show I used a landscape generator and an abstract image generator. The dataset for the landscape generator consists of landscape photos from google images, and rover photos from Mars, Venus, and Titan. I selected each image based on my taste, especially the ones that contained that feeling of absence I talked about earlier. For the abstract image generator, I selected images of all of my favorite paintings. Once the dataset is complete, each dataset contains thousands of images, and I begin training the AI on the dataset. During this training period, the AI looks for common patterns between all the images. The AI has no understanding of what is in the images, it only sees shapes. For example, in the landscape dataset the AI would think, there always seems to be a big blue shape in the top of these images, and to us this would be a sky. Once the AI has found many of these patterns, it can then generate original imagery. What I love about AI images is their emptiness. Technically, there is no authorship behind them. The lack of its understanding of what a mountain is, what a cloud is, etc. is shocking to see in an image. Snowy mountains morph into cumulus clouds, lake surfaces will have multiple sun reflections, trees will be levitating in the air, it is all completely alien. But now, I use this imagery in place of my own creativity. In essence I have outsourced the most sacred part of my art practice to a machine. What does this mean? Is it significant? I’m not sure, but I find it interesting. I found that if I only paint the AI image, it takes on a sci-fi feel, which isn’t my goal. I solved this problem by projecting the imagery onto my still life set, but in the process of doing this, it became a metaphor for my own creativity. The AI generators are an externalization of my own stream of thought. I cannot control or predict what images will flow through my mind, just as with the AI. I then project this stream of thought onto real objects, and together they are dissonant. The skewed projected landscapes are an analogy for my warped lens of subjectivity. And the alienness of looking into the imaginings of an AI, is probably similar to how someone else may view my own imaginings. Once again, I am externalizing my mind through painting.

Constructions

The collection of paintings called, “Constructions” appear as if I slung a bucket of hydrochloric acid onto western painting and melted out all the substance. This glistening Dairy Queen slurpy art is uncomfortably empty. The viewer’s mind scrabbles to resolve the ambiguities, but it cannot assign concepts to the imagery. What is this substance? Where is this space? What does it mean? I have hollowed out the genre and have left only the illusion. The absence of decipherable content, for me at least, frames realist painting in a new way. This imagery is also a metaphor for my revelation in the chapter, “The Tremendous Joy Simply of Being.” These paintings just are, as life for an atheist just is. They exist because of chance decisions made intuitively in my open-ended artistic process, rather than strict adherence to depicting a concept. I believe that mid-century Ab-ex paintings had the same goal. They sought a purity in painting through reducing it to just material on a surface. But the language of abstraction has lost the pizazz it once had, and I believe realism is now a better language for thusness. While this imagery may be empty for most viewers, and now I may be contradicting myself, for me they express the qualia of the time I was creating them. How can I fully express the range of thought and feeling I experience in just one day? That in itself could be a series of novels. Through this intuitive process of painting I have developed, I put my faith in my intuition to guide me. I do believe that they capture my mood of the time I was creating them. For example, the painting of the crumbling golden arch was painted in the summer of 2020 in my bedroom in Florida. The arch is a symbol of societal triumph, and I believe this motif arose from my unconscious to express my anxiety for American society in that moment. I imagined the image shortly after George Floyd was murdered. What a brutal time it was with the compounding crises of governmental corruption, covid, and societal unrest. We all watched the misery of our time play out through the cold distance of our tv screens and iPhones, while stuck in isolated lock down. Somehow this perfect image came out of my mind which embodied the mental states of that summer. Each image has that significance for me, but what is important for the viewer isn’t the story but the mood the images carry.